Across Asia, massive stones arranged by unknown hands challenge the way we think about ancient civilizations. Asian megaliths — from burial chambers in India to terraced pyramids in Indonesia — reveal forgotten traditions that suggest our ancestors may have been far more sophisticated than mainstream history allows.

India’s Megaliths: Tombs, Altars, and Astronomical Markers

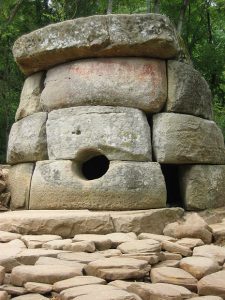

India has one of the richest concentrations of megalithic monuments in the world. Sites such as Hire Benkal in Karnataka, with more than 400 dolmens, stand as silent witnesses to a culture that thrived over 3,000 years ago. Archaeologists believe these dolmens were used for burials, but local traditions and alignments suggest they may also have served astronomical purposes, marking solstices or stellar positions.

Other megalithic sites in India include Menhirs in the northeast, stone circles in Maharashtra, and burial chambers in Tamil Nadu. The diversity of these monuments hints at a complex spiritual worldview where death, nature, and the stars were deeply connected.

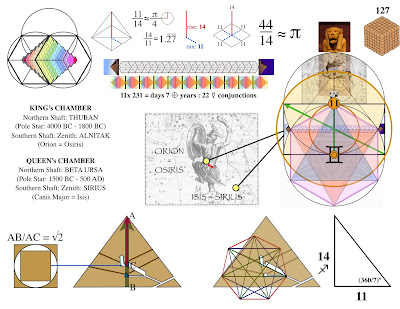

Could these dolmens have been more than tombs? Some researchers argue they encode cosmic knowledge, a tradition echoed in sacred geometry across cultures.

Gunung Padang: The Indonesian Enigma

High in the hills of West Java stands Gunung Padang, often called Southeast Asia’s most mysterious megalithic site. What appears to be a simple stone terrace may actually conceal something extraordinary: geological surveys suggest that beneath the visible site lies a stepped pyramid-like structure, potentially dating back 20,000 years or more.

If these findings are correct, Gunung Padang would predate all known civilizations, rewriting our understanding of human history. Like Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, this site may have been deliberately buried, possibly to preserve it through cataclysms such as comet impacts or massive climate shifts.

Its alignment with sacred directions and terraces designed for gatherings suggest it was a ritual center, a place where ancient people sought to connect with cosmic forces.

Japan’s Megaliths: Legacy of the Kofun

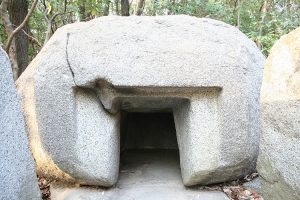

Japan, too, has its megalithic heritage. The most famous example is the Ishibutai Kofun in Asuka, a massive stone tomb built in the 6th century CE for a powerful clan leader. Constructed with giant granite blocks weighing over 70 tons, it rivals the engineering feats of other megalithic sites worldwide.

But Japan’s megalithic story may go deeper. Local traditions tell of stones aligned with celestial bodies and sacred landscapes tied to Shinto myths. Some researchers suggest the megalithic tradition in Japan has roots stretching back into prehistory, blending ancestor worship with sky-watching rituals.

Shared Knowledge or Separate Origins?

The spread of Asian megaliths — from dolmens in India to terraced pyramids in Indonesia and tombs in Japan — raises profound questions. Were these cultures truly isolated, each developing their own stone traditions? Or do the striking similarities point to a shared body of ancient knowledge passed along before written history?

One intriguing pattern: the older the megalithic site, the larger and more precise the stonework. This is the reverse of what we’d expect from a simple “linear progression” of technology. Instead, it suggests that cataclysms, cultural disruptions, and the loss of ancient libraries may have interrupted the flow of knowledge. Humanity may not have advanced in a straight line, but in cycles of rise, collapse, and rediscovery.

A Call to Rethink Human History

Asian megaliths are more than stones — they are messages from the deep past. Their alignments with stars, their enduring presence through thousands of years, and their mysterious functions remind us that ancient cultures may have been far more advanced, spiritual, and interconnected than mainstream history admits.

As new discoveries emerge — like evidence of comet airbursts 12,800 years ago that may have reshaped global civilization (Phys.org, 2024) — we may find that the story of human progress is not a straight line, but a tapestry woven with forgotten chapters.

Additional readings: