The Cosmic Vision of the Maya

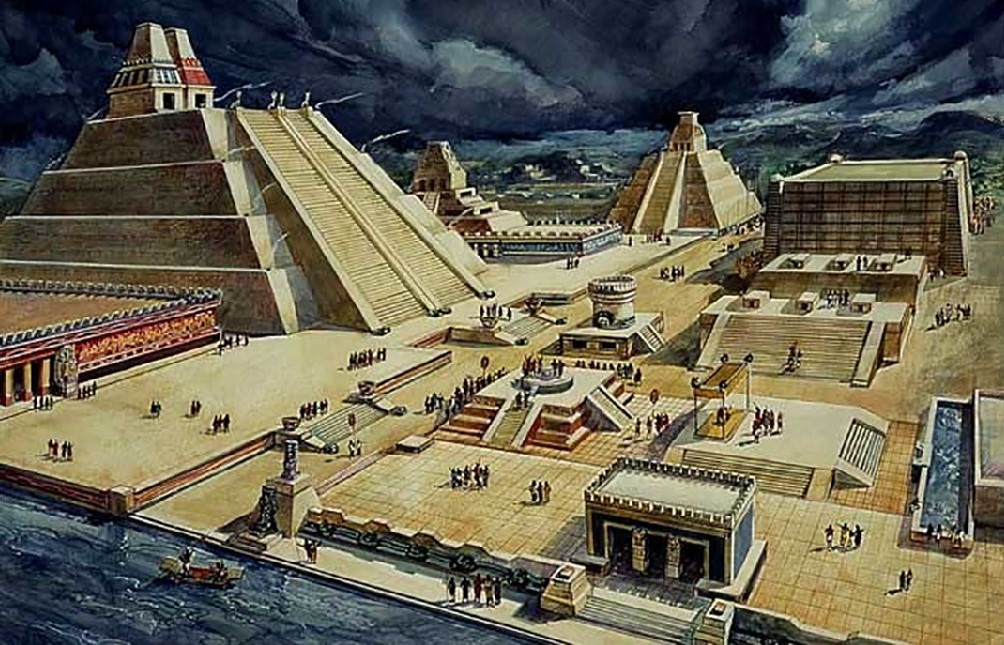

In the book Archaeoastronomy and the Maya, a collection of scholarly papers reveals how astronomical observation shaped the urban design and worldview of the ancient Maya. The positioning of temples and cities was not random — it reflected a sophisticated cosmological understanding that linked human order to celestial motion.

The layout of Maya centers integrated social, environmental, and ideological dimensions, showing how cosmic principles were literally built into the landscape.

Tracking the Sun: The Origins of the Maya Calendar

Research by Harold Green explores the origins of Maya calendrics at Chocolá, Guatemala, during the Preclassic period. He argues that the site’s design — oriented to the sun’s movement along the horizon — may have inspired the 260-day Tzolk’in count and the 365-day Haab’ calendar. Chocolá’s strategic placement allowed observation of solar rise points during equinoxes and solstices, possibly acting as an early astronomical observatory.

This system of solar tracking would later influence the precise alignment of major Maya temples and civic structures throughout Mesoamerica.

Celestial Patterns and Agricultural Rhythms

Further insights come from Ivan Šprajc’s fieldwork across southeastern Campeche, where he studied eleven ancient Maya sites. His findings reveal a regional pattern of solar alignments dividing the year into intervals of 260 and 105 days — intervals crucial for agricultural cycles.

Šprajc suggests that these early alignments in Campeche predate similar patterns in Central Mexico, implying that the “17°-family of orientations” known in Mesoamerica may have originated within the Maya cultural sphere itself.

The Temple of the Sun: Light and Architecture at Palenque

One of the book’s most compelling studies focuses on the Cross Group at Palenque, particularly the Temple of the Sun. Here, solar light interacts with architectural symmetry to mark events such as the summer solstice, equinox, and zenith passages of the sun.

During the reign of K’inich Kan B’ahlam II (AD 684–702), architects designed temples that functioned as both ritual centers and astronomical instruments — aligning light and shadow to encode celestial cycles into stone.

Interpreting the Heavens through Technology

Researchers Alonso Méndez and Carol Karasik use planetarium software to digitally reconstruct the sky as seen by the Maya. By converting ancient Maya dates to Julian and Gregorian equivalents, they demonstrate how celestial events — eclipses, solstices, planetary positions — correspond to recorded inscriptions and iconography.

This integration of modern astronomy and epigraphy offers a window into how the Maya understood cosmic order as both mythic narrative and empirical science.

A Celestial Blueprint for Civilization

Collectively, the essays in Archaeoastronomy and the Maya demonstrate that solar and stellar observation was central to Maya civilization — not as passive sky-watching, but as a practical, agricultural, and spiritual discipline.

Temples were often positioned near natural horizon markers, such as mountain peaks, allowing priests to track solar events and plan rituals or crop cycles accordingly. These architectural alignments — skewed slightly clockwise from the cardinal points — reveal an intentional synthesis of science, religion, and political ideology.

The result is a cultural blueprint where astronomy shaped not only the calendar but the very fabric of urban space, linking heaven and earth through architectural precision.

Conclusion

For the ancient Maya, the cosmos was not an abstract domain but a living map embedded in their cities, rituals, and sense of time. The work compiled in Archaeoastronomy and the Maya shows how their builders, astronomers, and priests united practical observation with sacred meaning — creating one of the most advanced sky-oriented civilizations of the ancient world.

Additional reading

References

– Ashmore, W. & Sabloff, J. A. (2002). Spatial Orders in Maya Civic Plans. Latin American Antiquity, 13(2): 201–215.

– Aveni, A. F. (2001). Skywatchers. Austin: University of Texas Press.

– Gronemeyer, S. (2006). Glyphs G and F: Identified as Aspects of the Maize God. Wayeb Notes 22.

– Hallowell, I. A. (1977). Cultural Factors in Spatial Orientation. In Symbolic Anthropology, Columbia University Press.

– Schele, L. & Miller, J. H. (1983). The Mirror, the Rabbit, and the Bundle. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

– Thompson, E. S. (1929). Maya Chronology: Glyph G of the Lunar Series. American Anthropologist, 31: 223–231.