The Origins of Atlantis

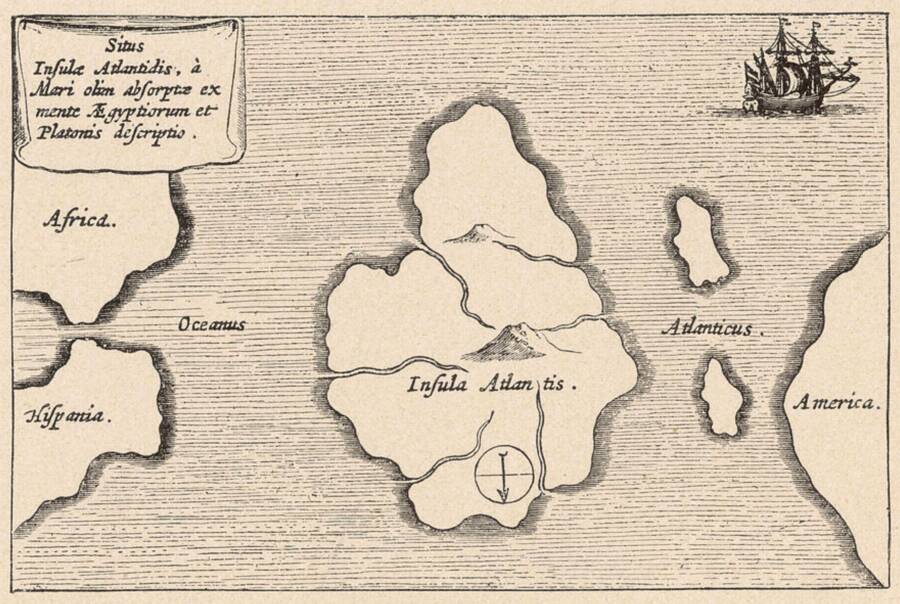

The story of the lost island of Atlantis comes from two Socratic dialogues, Timaeus and Critias, written around 360 BCE by the Greek philosopher Plato. These dialogues formed a festival speech to be told on the Panathenaea, honoring the goddess Athena. Plato describes a conversation between Socrates, Timaeus of Locri, Hermocrates of Syracuse, and Critias of Athens.

Critias recounts how his grandfather met Solon, the Athenian poet and lawgiver. During his travels to Egypt around 590 BCE, Solon learned about Atlantis from Egyptian priests in Sais. They described a civilization that existed approximately 9,000 years before their time, suggesting that Atlantis thrived around 9,600 BCE.

Geography and Layout of Atlantis

Plato describes Atlantis with striking detail. The central city sat on a plain surrounded by mountains. Concentric rings of land and water encircled the city, connected by wide tunnels to allow easy naval movement. The plain featured fertile soil irrigated by canals, abundant minerals, and natural springs.

At the center of the rings, a hill held a palace for the first king, Atlas, after whom the island was named. Surrounding the palace, walls of red, white, and black stone, decorated with precious metals, showcased the wealth of Atlantis. Beyond the city, the island divided into ten regions, each governed by a king.

Society and Culture of Atlantis

Atlantis featured a hierarchical yet collaborative society. Ten kings, descendants of the island’s divine founders, ruled the regions. They convened in the central city to make decisions about law, war, and peace. Their judgments were binding, and they swore oaths to uphold the island’s laws.

The Atlanteans excelled in maritime skills, controlling trade routes and exerting influence over parts of Europe and Africa. They worshipped a pantheon of gods, led by Poseidon, the god of the sea. Atlantis thrived as a technologically advanced, prosperous, and culturally sophisticated civilization.

The Destruction of Atlantis

Plato explains that Atlantis met a sudden and catastrophic end. In a single day and night, earthquakes, floods, or possibly meteor impacts sank the island beneath the sea. The survivors disappeared, leaving only Plato’s account as evidence.

This rapid destruction captures the imagination, suggesting how vulnerable even the most advanced civilizations can be to natural events.

Modern Theories and Connections

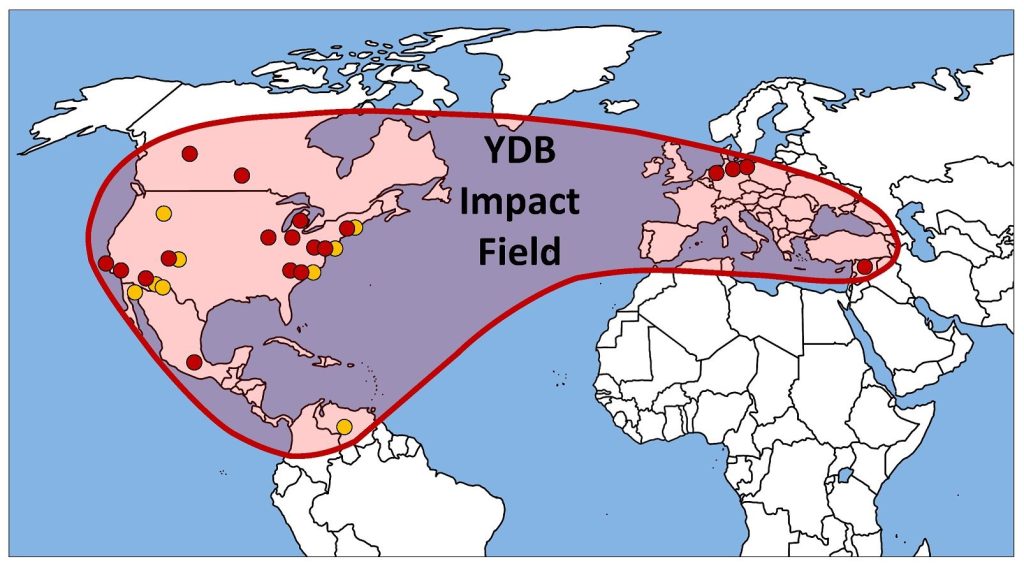

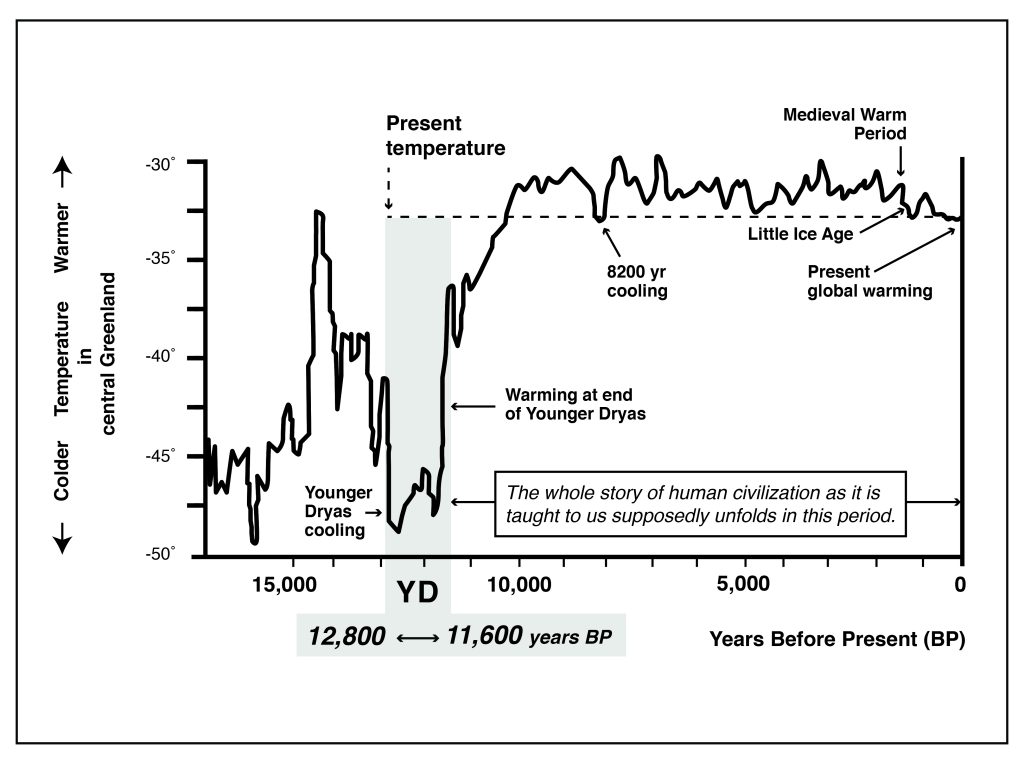

Researchers have explored possible connections between Plato’s account and real-world events. The Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis (YDIH) proposes that sudden climate shifts and meteor impacts caused widespread destruction. This theory aligns with the sudden catastrophe described in Atlantis’ story.

Similarly, ancient maps such as the Piri Reis Map, the Buache Map, and the Oronteus Finaeus Map hint at forgotten knowledge of continents and pre-Ice Age conditions. Just as these maps challenge our understanding of ancient exploration, Plato’s Atlantis encourages us to reconsider what ancient civilizations may have known.

Further Reading

-

Donnelly, Ignatius. Atlantis: The Antediluvian World. Book Tree, 2006.

-

Gill, Christopher. “The genre of the Atlantis Story.” Classical Philology 72, no. 4 (1977): 287–304.

-

Zink, David. The Stones of Atlantis. Prentice-Hall, 1978.

-

Continue exploring related sources on ancient maps and civilizations at Ancient 360.

Final Thoughts

The most recent studies accumulate evidence in support of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis (YDIH) that could connect Plato’s story of Atlantis and the respective dates. Plato writes that Atlantis perished in a great catastrophe that submerged it beneath the waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Plato also describes the event that destroyed Atlantis “in a single day and night” because of “violent earthquakes and floods” that might connect to earthquakes followed by tsunami after meteor impacts. There are many aspects of the Younger Dryas Impact Hypothesis that fit with a classic Greek story, not Plato’s story of Atlantis though. The story they fit is The Story of Phaeton.

References

- Forsyth, P. Y. Atlantis: The Making of Myth. (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1980), p. 12

- Timaeus, 3b

- Plato, The Republic, v, 515b2

- Forsyth, p. 18

- Critias. 32 b

- Forsyth, p. 18

- Castleden, Rodney. Minoans: Life in Bronze Age Crete (New York, Routledge, 1993), p 13-30

- Castleden, p. 113

- Castleden, p. 117

- Chamorro, Javier G. “Survey of Archaeological Research on Tartessos”. American Journal of Archaeology. 91 (2): (1987) 197–232

- Morgan KA. 1998. Designer History: Plato’s Atlantis Story and Fourth-Century Ideology.The Journal of Hellenic Studies 118:101-118.

- Rosenmeyer TG. 1956. Plato’s Atlantis Myth: “Timaeus” or “Critias”? Phoenix 10(4):163-172