Turkey is hailing the discovery of an 11,400-year-old monumental site as one of the world’s oldest villages, the oldest known gathering complex. First discovered in 1963 by a Turkish-American archaeological survey directed by Halet Çambel and Robert Braidwood, the excavation of Göbekli Tepe would only begin in 1994-95. This is when the pillars were first discovered by the German archeologist Klaus Schmidt. More sites featuring T-shaped pillars were subsequently discovered, among them Karahan Tepe in 1997.

Potbelly Hill in Turkish, Göbekli Tepe is an artificial mound spread across eight hectares at the top end of the Fertile Crescent near the present-day city of Sanliurfa, Turkey. The oldest known gathering complex is a Neolithic archaeological site located in the Southeastern Anatolia Region of Turkey. Dated between c. 9500 and 8000 BCE, the site comprises several large circular structures supported by massive stone pillars. Some call Göbekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe, and other monumental Neolithic sites the earliest temples in the world. Others point out that it’s hard to know what prehistoric people were thinking. Göbekli was the first to be found. Subsequently, 11 more such sites were reported. And experts say there are at least 16 big ones, Gobekli and Karahan both being big, and a lot of small campsites.

All the big sites feature T-shaped stone pillars, some of them giant and all like nothing found anywhere else – not then and not later. At Göbekli, the most extensively excavated of these sites, the tallest pillar is 6 meters high. Many are engraved with stylized human and animal reliefs. For reasons unclear, periodically throughout this culture’s lifetime, it seems the active stone enclosures would be buried deliberately or by forces of nature and a new one erected. This is how the art at Göbekli Tepe has survived, buried for longer than 10,000 years. The pillars bear reliefs of humanoid forms wearing belts, necklaces and loincloths seemingly fashioned of pelts. The humanoids have strange numbers of fingers – never five. The animal images: a vulture, lizards, boars, spiders, scorpions, foxes, leopards, crocodiles. These monoliths predate Stonehenge and Rujm el-Hiri in Israel by as much as 6,000 to 7,000 years and seem vastly more sophisticated.

Once heaven, the structures evoke awe.

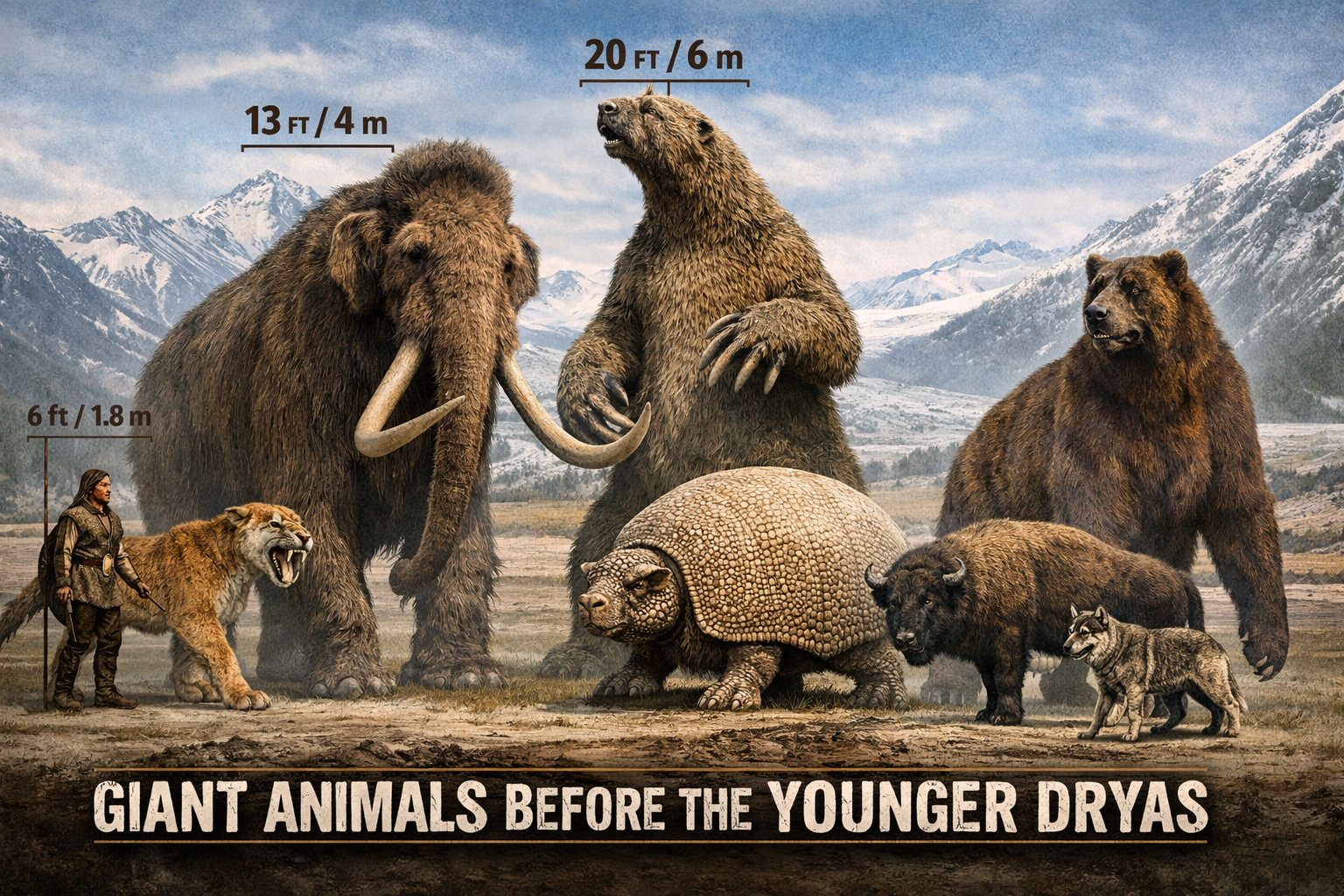

If these great standing T-shapes represent gods, they are gone. If they represent ancestors, they are forgotten. If they are stylized mirrors of the world around, their world is long gone too. The hills, once forested and teeming with wild animals, are eroded. Some soil clings to the hilltops: these remnants are archaeological deposits. The rest was washed downhill into the valleys and plains. The region had been wetter in the Neolithic. Now the land isn’t crossed by bubbling brooks and rivers but irrigation canals, bringing water from the Euphrates River. No trace remains of the trees that had thrived when this land had been a post-Ice Age paradise.

But what are these places? Assuming that Göbekli, Karahan, and the other monumental prehistoric sites in southeastern Turkey must be “temples” closes the mind. It underestimates their function. If one must generalize, these structures were “gathering places” located in the fertile crescent. Located between two climate zones that could have teamed with animals and plants flourished; the hunter-gatherers didn’t need to forage far, and their economy had “grown beyond its natural hunter-gatherer context,” and peoples would have encountered one another, gaining new worldviews, technologies, traditions, beliefs, and ideas. Although the creators of Göbekli Tepe were still foragers and hunters, their hierarchies and societies might have grown in status.

2 Responses