The Piri Reis Map and the Impossible Coastlines

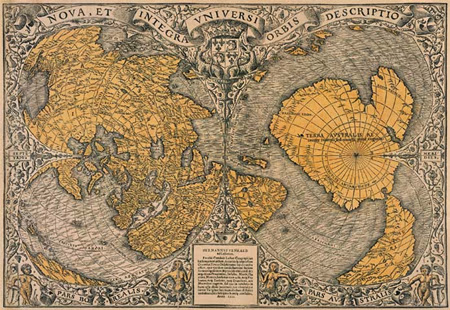

The Piri Reis map history occupies a unique and controversial position within the study of ancient maps, not because it is mysterious in isolation, but because it appears to preserve geographical knowledge that should not have been available to early sixteenth-century cartographers operating within the technological and conceptual limits of their time. Compiled in 1513 by the Ottoman admiral and cartographer Piri Reis, this fragmentary world map raises enduring questions about lost sources, inherited knowledge, and whether ancient maps sometimes functioned as repositories of information transmitted across forgotten civilizations.

The Historical Context of the Piri Reis Map

Piri Reis was not an obscure or fringe figure; he was a highly trained naval commander within the Ottoman Empire, deeply involved in Mediterranean and Atlantic navigation, and well acquainted with the cartographic traditions of both the Islamic and European worlds. The map itself was drawn on gazelle skin parchment and rediscovered in 1929 at the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul, where it had remained unnoticed for centuries.

Crucially, Piri Reis left detailed marginal notes explaining his methodology. He explicitly stated that the map was compiled from approximately twenty earlier charts, including Arabic maps, Portuguese portolan charts, and—most provocatively—older maps dating back to the time of Alexander the Great. This admission alone places the Piri Reis map history firmly within a lineage of inherited cartographic knowledge rather than a single act of Renaissance innovation.

Impossible Coastlines and Geographical Accuracy

What elevates the Piri Reis map beyond historical curiosity is the remarkable accuracy of certain coastal outlines, particularly along South America and parts of Africa, which align more closely with modern longitudinal measurements than should be possible prior to the invention of accurate marine chronometers in the eighteenth century.

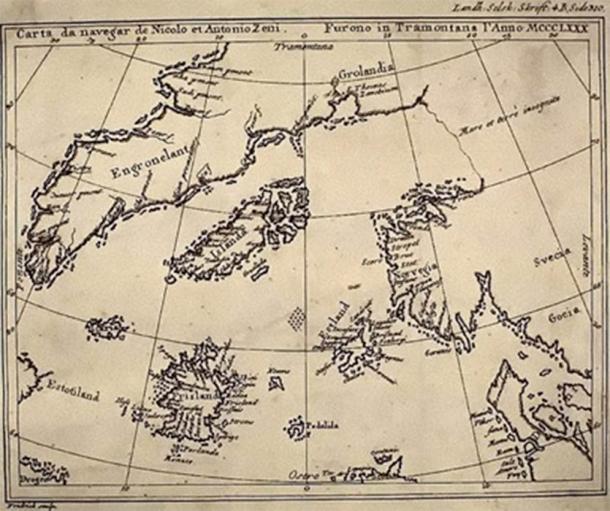

Even more controversial is the southern portion of the map, which appears to depict a landmass resembling Antarctica—shown without its modern ice cover. While critics argue this represents a distorted extension of South America, proponents note that the coastline bears striking similarities to subglacial Antarctic profiles mapped only in the twentieth century using seismic and radar technologies.

If the southern landmass is indeed Antarctica, then the implications for ancient maps are profound, suggesting the existence of a prehistoric source culture capable of coastal surveying during a period when Antarctica was at least partially ice-free, likely prior to the end of the last Ice Age.

Sources Older Than the Map Itself

The Piri Reis map history becomes even more compelling when examined through the lens of source inheritance. Piri Reis did not claim originality; instead, he described himself as a compiler of older knowledge. This aligns with a broader pattern seen in ancient maps, where later cartographers preserved fragments of much older geographic data, often without fully understanding their origin.

Several scholars have proposed that some of these source maps may date back to a high-level maritime civilization existing during the late Pleistocene, when sea levels were significantly lower and coastlines vastly different from those of today. If true, this would explain why certain submerged continental shelves and drowned landmasses appear more accurately rendered in ancient maps than in medieval reconstructions.

Ancient Maps and the Memory of a Different World

One of the most overlooked aspects of the Piri Reis map history is its potential role as a memory device—a cartographic fossil preserving a vision of the world before dramatic climatic and geological transformations reshaped Earth’s surface. During the Younger Dryas and subsequent meltwater pulses, rising seas erased vast coastal plains, forcing human populations inland and submerging entire landscapes beneath the oceans.

Ancient maps, in this interpretation, are not speculative fantasies but degraded records of a world that no longer exists, filtered through centuries of copying, translation, and reinterpretation. The Piri Reis map may therefore represent not discovery, but remembrance. Could this be another example of a lost civilization? Ancient maps of a drowned world, echoes of a lost civilization?

Cartography Before Modern Science

From a purely technical standpoint, the Piri Reis map history challenges conventional narratives about the evolution of cartography. The projection methods implied by the map suggest a sophisticated understanding of spherical geometry, yet no historical record exists of such techniques being formally developed at the time.

This discrepancy forces a reconsideration of how scientific knowledge progresses. Rather than a linear ascent from ignorance to enlightenment, the evidence from ancient maps suggests cycles of accumulation, loss, and rediscovery—where advanced knowledge can vanish, only to resurface in fragmentary form generations later.

Why the Piri Reis Map Still Matters

The enduring significance of the Piri Reis map lies not in proving a single extraordinary claim, but in destabilizing the assumption that modern civilization represents the first apex of human knowledge. When viewed alongside other anomalous ancient maps, the Piri Reis map history points toward missing chapters in humanity’s past—chapters marked by seafaring, global awareness, and an understanding of Earth that predates recorded history.

For Ancient360, this map serves as a cornerstone example of why ancient maps deserve renewed scrutiny, not as myths or curiosities, but as data points in a much larger, unfinished story about the true antiquity of human knowledge.

Additional readings and sources

-

Piri Reis, Kitab-i Bahriye (Book of Navigation) – link

-

Hapgood, C.H., Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings – link

-

National Library of Turkey – Piri Reis Map Archives

-

NOAA studies on subglacial Antarctic coastlines

- The Younger Dryas Abrupt Change – link

-

Scientific American – Historical cartography and pre-modern navigation