The Zeno Map History and the Problem of Forgotten Geography

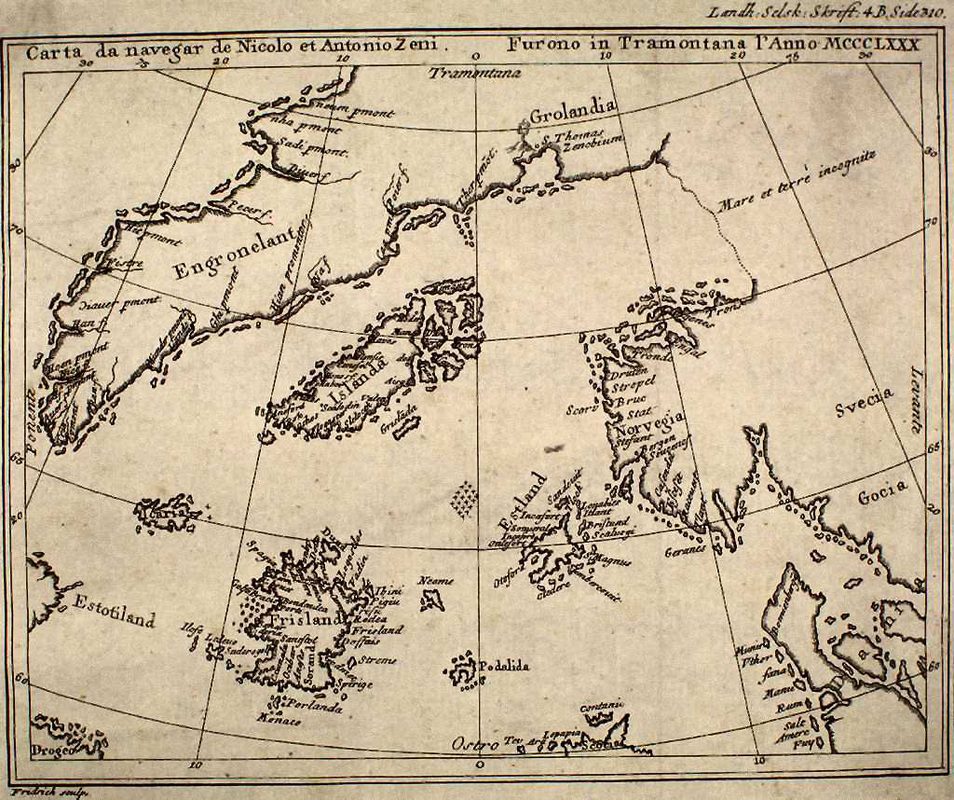

The Zeno Map history occupies a controversial yet fascinating position within the study of ancient maps. First published in 1558 by Nicolo Zeno the Younger, the map was claimed to be based on far older navigational charts and letters written by his ancestors, the Venetian brothers Nicolo and Antonio Zeno, who allegedly voyaged through the North Atlantic in the late 14th century.

What makes the Zeno Map remarkable is not merely its age, but its depiction of lands, islands, and coastlines that either do not exist today or appear grossly misplaced when compared to modern geography. For critics, this makes the map unreliable. For others, it raises a more unsettling question: does the Zeno Map preserve fragmented memories of a geography that has since been altered or submerged?

Origins of the Zeno Map

According to Nicolo Zeno the Younger, the map was reconstructed from damaged manuscripts and charts discovered in his family archive. These documents allegedly described voyages across the North Atlantic decades before Columbus, detailing regions such as Greenland, Iceland, and a series of unknown islands labeled Frisland, Estotiland, and Drogeo.

The Zeno Map history begins, therefore, not as a Renaissance invention but as a medieval narrative rediscovered and republished centuries later. This gap between origin and publication is one of the main reasons historians remain divided about its authenticity.

Frisland: A Phantom Island or Lost Land?

The most controversial feature in the Zeno Map history is Frisland, a large island shown south of Iceland. Frisland appears with detailed coastlines, cities, and harbors, suggesting prolonged human familiarity rather than speculation.

Modern geography offers no such island. However, similar landmasses appear on multiple medieval maps for over two centuries. This consistency raises the possibility that Frisland may represent:

-

A misinterpreted Greenland coastline

-

A now-submerged landmass affected by post-glacial sea-level rise

-

A composite of several islands remembered through oral tradition

Rather than dismissing Frisland outright, some researchers argue it reflects an unstable North Atlantic geography during the Late Medieval Warm Period and subsequent climatic shifts.

Greenland Before the Ice

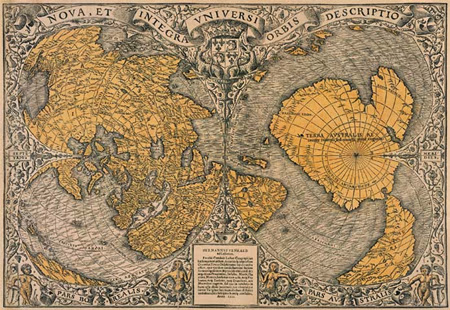

One of the strongest arguments in favor of the Zeno Map history as preserved knowledge is its portrayal of Greenland. Unlike modern maps, Greenland is shown with extensive coastlines and navigable waters, implying ice-free conditions. This depiction aligns with independent paleoclimatic evidence suggesting that Greenland experienced warmer conditions during parts of the medieval period. It also parallels controversial claims surrounding other ancient maps that depict ice-free polar regions, suggesting access to far older source material.

Viking Knowledge and Lost Navigational Traditions

The Zeno Map history gains further credibility when viewed through the lens of Viking exploration. Norse sailors reached Iceland, Greenland, and North America centuries before Columbus. Their navigational knowledge, passed orally or through rudimentary charts, may have influenced later medieval cartographers.

If the Zeno brothers encountered remnants of Viking routes or settlements, the map may represent a hybrid record: part direct observation, part inherited geographic memory.

Cataclysm, Climate, and the Disappearance of Lands

The North Atlantic has been profoundly shaped by glacial cycles, sea-level rise, and tectonic instability. Large areas of continental shelf were exposed during the last Ice Age and later submerged as glaciers melted.

Within this context, the Zeno Map history may preserve distorted recollections of lands that existed before catastrophic flooding reshaped coastlines. What modern scholars label “errors” may instead be traces of a drowned world no longer visible.

Criticism and Skepticism

Mainstream historians often argue that the Zeno Map is a 16th-century fabrication or a heavily altered reconstruction influenced by later cartographic knowledge. Errors in latitude, inconsistent island placement, and stylistic elements fuel this skepticism.

Yet dismissal alone does not explain why multiple phantom islands appear consistently across unrelated medieval maps, nor why navigational details often align with real oceanic conditions.

Why the Zeno Map Still Matters

The importance of the Zeno Map history lies not in proving every detail correct, but in challenging assumptions about what medieval and ancient people knew—or remembered—about the world.

Like many ancient maps, it suggests that geography is not only shaped by land, but by memory, catastrophe, and transmission across generations. The Zeno Map stands as a reminder that human history may contain erased chapters, hidden beneath rising seas and forgotten by official narratives. The concept of the Zeno Map is another reminder of culture, information, clues, received from a very possible ancient civilization that might have mapped the planet before our most recent discoveries… or, re-descoveris. Echoes of lost civilizations?

Additional Readings & Sources

-

Zeno, N. (1558). Dello Scoprimento dell’Isole Frislanda – link

-

Skelton, R.A. – Explorers’ Maps: Chapters in the Cartographic Record of Geographical Discovery

-

National Library of Denmark – Medieval North Atlantic Cartography

-

Britannica – Zeno Brothers and the Zeno Map – link

-

Geological studies on North Atlantic sea-level changes and submerged shelves